Strategies for Health and Long-term Sustainable breeding

In the revised Breeding Strategies (Rasspecifika Avelsstrategier - RAS), the Swedish Rhodesian Ridgeback Club, in collaboration with a vast majority of the Swedish breeders, has decided that one of the action plans is to support ridgeless dogs (with genotype r/r) being used in breeding under certain conditions, with the purpose to better maintain genetic diversity in the breed. This decision has gone viral in various Ridgeback Forums online and is being widely debated, which is why we share the reasoning behind the decision in English.

-----

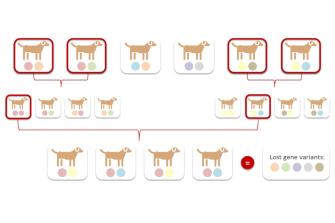

One of the most important factors to ensure a long-term sustainable breed is to maintain a sound breeding structure in which as much genetic diversity as possible is preserved within the population. Genetic diversity is vital for the adaptability and survivability of the population. A decrease in genetic diversity increases the risks of hereditary diseases, immune deficiency and infertility. When there is a lack of genetic diversity in a population it is extremely difficult to come to terms with health issues as well as other undesirable traits that occur within the breed, as it is simply not possible to make appropriate breeding selections if all individuals carry the same gene variant for a certain characteristic.

In a closed population, which is the case in all pure-bred dogs, new gene variants (alleles) generally are not introduced. Most of the gene variants in our present dogs can theoretically be traced back to at least one of the individuals who founded the population when the studbooks were closed almost 100 years ago.

Many individuals doesn't guarantee a broad gene pool

The fact that a breed consists of many individuals does not guarantee a broad gene pool with many unrelated dogs and bloodlines available for breeding. In Sweden, more than 40% of the litters have at least one parent born in another country. Unfortunately, this doesn’t significantly contribute to genetic diversity, as most of these individuals still have the same dogs in their pedigrees, just a few generations back. Since the studbooks are closed and the population is limited, it is crucial to include as many individuals in breeding as possible (instead of one individual being used many times).

Every individual carries a distinct combination of genes that make up its genome. The genome contains the complete set of genetic instructions for the development and functioning of that particular dog. When a dog is used for breeding, it passes on a portion of its unique genetic material to its offspring. This is a fundamental process in reproduction, where genetic information is transmitted from one generation to the next. Despite having the same parents, siblings (dogs born from the same litter) do not possess identical sets of genes. This is due to the process of genetic recombination (also called genetic reshuffling), where genetic material from both parents combines and shuffles during the formation of reproductive cells (sperm and egg). During the formation of reproductive cells, chromosomes exchange genetic material, leading to new combinations of genes in the offspring. As a result, each sibling inherits a unique combination of genes from their parents, and thus diversity arises among siblings even when they share the same parents.

Consequently, every time we choose to exclude a healthy and mentally sound dog from breeding, there is a risk that we permanently lose gene variants that could have been beneficial to the breed. In the best interest of the breed, we must do our utmost to preserve as much genetic diversity as possible. This could help prevent increasing health problems in the future.

Managing diseases with unknown genetic cause

The majority of genetically inherited diseases in our dogs (all breeds) have an unknown inheritance pattern that is often complex (polygenic), caused by several genes, and sometimes environmental factors in combination. Examples of such diseases include allergy, idiopathic epilepsy, hypothyroidism, SLO (symmetrical lupoid onychodystrophy), osteochondrosis, cancer, and more. All Rhodesian Ridgebacks – yes, all! – carry gene variants that may predispose them to certain diseases that occasionally occur in our breed. Usually, they also possess a non-mutated variant of the same gene (a wild-type allele) preventing them from illness. However, they can still pass on a potentially unfavourable variant to their offspring.

Since we cannot gene test for these diseases, and thus avoid specific breeding combinations, we must try to ensure that there are as many different gene variants as possible within the breed to avoid homozygosity (two identical variants of a gene) in general. We cannot achieve this by excluding healthy dogs from breeding since they also carry beneficial gene variants. Instead, we must try to avoid breeding combinations where both breeding animals, based on accessible information about themselves and their relatives (such as parents, siblings, and offspring), have an increased risk of carrying gene variants that predispose them to the same type of disease. It's like a jigsaw puzzle. When a dog gets sick it's very sad but not a sin (provided we've done what we can to avoid it) – it's knowledge!

Main focus should be on the the progeny

With this reasoning, the Swedish Rhodesian Ridgeback Club (SRRS) has decided to support that breeders use ridgeless dogs with genotype r/r in breeding, provided it is bred to a ridged dog with genotype R/R. But of course, it’s completely voluntary to use a ridgeless dog for breeding.

Including genetically ridgeless dogs in breeding is in no way an attempt to change the breed standard, which states that a Rhodesian Ridgeback should have a ridge. On the contrary, the aim is to, with today's knowledge and tools, better meet the requirements of the breed standard (in terms of the ridge) while continuing to keep down, but unfortunately not eliminate, the risk of dermoid sinus and try to maintain genetic diversity. The breed standard is the ideal image of the dogs we should strive to breed, but it doesn’t have to be synonymous in all respects with the ideal image of the individuals we use for breeding to achieve the desired result. Our main focus should be on the result of the breeding - the progeny – rather than on the breeding animals.

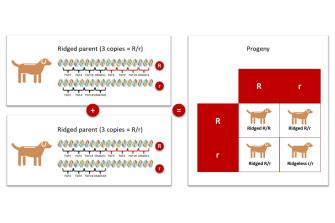

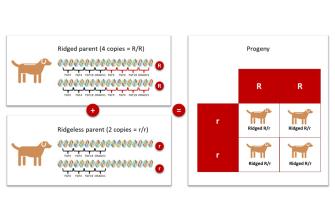

The ridge occurs on chromosome 18 through a duplication of four genes (FGF3, FGF4, FGF19 and ORAOV1) and a part of a fifth (CCND1) in the said order. Dogs normally have two sets of these genes, one from each parent, which means they are genotypically r/r and do not display a ridge on their backs. In some cases, there is a duplication – an extra copy – of these genes, in which case the dog has a ridge. The dog only has to get this duplication from one parent, having three sets of said genes, for the ridge to occur. Carelessly, we call this the “ridge gene”, and the inheritance is autosomal dominant.

In a breeding combination involving a genotypically ridgeless dog (r/r) and a ridged homozygote individual (R/R), all resulting puppies are expected to be genotypically heterozygous (R/r) and, according to standard expectations based on Mendelian inheritance pattern, should exhibit the ridge. However, it is observed that about 5 % of the heterozygous dogs (R/r) may not express the ridge physically, despite carrying the genetic code for it. The underlying reason for this phenomenon remains unknown. Even with this consideration, a combination of ridgeless r/r and ridged R/R is anticipated to yield a higher percentage of true-to-standard, ridged puppies compared to a combination of two ridged dogs who are genotypically R/r, where statistically 25% of the offspring should be ridgeless.

We advise against using ridgeless heterozygotes (R/r) for breeding, as an unknown factor in their genetic makeup prevents the ridge from being expressed. Until the cause is identified, deliberate propagation of this trait within the population is avoided, out of respect for the breed standard.

Concerning dogs with ridge faults, there seems to be no compelling reason for their exclusion from breeding in the long run. However, a cautious approach is preferred, introducing changes incrementally and evaluating outcomes before deciding on future breeding strategies.

Collaboration between clubs and breeders

The inclusion of genotypically ridgeless (r/r) dogs in breeding will not alone have a substantial impact on the genetic diversity of the breed. To truly enhance genetic diversity, it is crucial to consider additional strategies. One such approach involves regulating the number of progeny and grand progeny for individual dogs, which can contribute significantly to maintaining a diverse gene pool. Expanding the breeding pool by involving several individuals, including those with distinct genetic backgrounds, is paramount for preserving overall genetic diversity within the breed. While the inclusion of genotypically ridgeless dogs is a positive step, it is just one facet of a comprehensive breeding strategy. By combining this recommendation with other essential breeding guidelines, we aspire to provide breeders of the next generation with a well-rounded set of tools. These tools aim not only to address immediate concerns but also to safeguard the genetic integrity and overall well-being of both individual dogs and the breed as a whole.

It is important to note that the SRRS is not pushing other breed clubs to include ridgeless dogs in breeding; rather, this is a decision left to the discretion of each club and its breeders. However, the emphasis is placed on collaboration between clubs and breeders to actively work together, avoiding unnecessary exclusions of healthy dogs from breeding and preventing the overrepresentation of individual dogs in breeding programs. Continuous education is encouraged, empowering clubs and breeders to find ways to preserve as much genetic variation as possible of what is still left within the breed.

Extract from the Breeding Strategies of the Swedish Rhodesian Ridgeback Club

Below are the SRRS breeding recommendations regarding breeding animals and combinations (in addition to Swedish laws and regulations and the rules of the Swedish Kennel Club). These recommendations are based on a large amount of data, such as population statistics, litter statistics, annual health surveys, insurance statistics and mentality assessments, that have been collected on the Swedish Rhodesian Ridgeback population for decades. These guidelines are further informed by foundational principles of population genetics and preservation breeding.

- The number of litters for each breeding animal should be minimized. Instead of using one individual dog in breeding multiple times, other individuals (such as siblings and offspring) should be used.

- Each individual breeding animal should not have more than 40 progeny or 80 grand progeny in Sweden. The number is based on the current population size in the country (on average approximately 400 registered dogs per year).

- Each individual should not have more than 20 progeny, or two litters if the litter size exceeds 8 puppies before the offspring have reached 24 months of age and their health and mentality have been evaluated (e.g. HD/ED-scoring, mentality assessment).

-

Breeding animals should be at least 30 months of age at the time of mating, with a preference for delaying breeding until 36 months (3 years) and preferably even later.

This approach increases the generation interval, slowering the loss of genetic diversity. Delaying the breeding debut also allows us to have more information about the breeding animals and their relatives when making a breeding combination. A later debut increases the chances of identifying and avoiding health issues in the breeding animals and their relatives. This allows the breeders to make wise, fact-based breeding decisions and minimize the risk of doubling up on hidden disease predisposition, thus preventing health issues in the progeny.

-

Breeding animals should be free from congenital diseases and chronic health issues with no reliance on special diets, continuous treatment or medical intervention to be symptom-free.

-

Breeding combinations should avoid situations where both breeding animals, based on accessible data regarding themselves and their relatives, may be suspected to carry gene variants that predispose to the same or closely related diseases or defects.

- Breeding animals should have HD grade A, B, C or equivalent. Those with HD grade C should be officially scored in Sweden, be bred to a dog who is officially scored in Sweden with HD grade A, have a maximum of 20 progeny or two litters if the litter size exceeds 8 puppies and have known HD status in 75% of the progeny from the first litter before the second breeding occurs.

- Breeding animals should have ED grade 0 or equivalent.

-

A ridgeless dog confirmed to be genetically ridgeless (r/r) through DNA-test should be bred to a ridged dog confirmed to be genetically homozygote (R/R) for the ridge gene before breeding.

-

A ridgeless dog confirmed to be genetically heterozygote for the ridge gene (R/r) should be avoided from breeding to prevent the potential spread of gene-silencing traits and the undesired increase of heterozygous (R/r) ridgeless dogs.

- A ridged dog who is confirmed genetically homozygote (R/R) for the ridge gene should be bred to a ridged dog who, before mating, is confirmed genetically heterozygote (R/r) or a dog who is genetically ridgeless (r/r), to lower the risk of dermoid sinus.

-

A dog with a mismarked ridge, including a single crown, extra crowns or extremely short ridge, should be avoided in breeding.

-

A Swedish registered breeding animal should have attended a “Behavior and personality assessment” (BPH) before mating, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of behavioural traits.

-

A breeding combination should aim to produce progeny with a higher degree of social and environmental security than the breed average. The mentality index based on BPH is recommended as a tool for this purpose.

-

The COI of a litter should not exceed 1% based on a five-generation pedigree. Exceptions should be rare and, when necessary, not exceed 3,1%.

-

A breeding combination that has been previously made should not be repeated, and combinations closely related to existing litters should be avoided.

-

No dog (male or female) should be neutered except for the purpose of alleviating or curing illness, as this reduces the gene pool and limits the ability to preserve genetic diversity. Neutering, especially at younger age, may also have several negative effects on both health and behavior.

Text: Jessica Persson, Veronica Thorén & Mona Hansen